Members of First Nations communities are respectfully advised that several people mentioned in this article have passed away.

“Today we stand in footsteps millennia old. We acknowledge the traditional owners whose cultures and customs have nurtured, and continue to nurture, this land, since men and women awoke from the great dream. We honour the presence of these ancestors who reside in the imagination of this land and whose irrepressible spirituality flows through all creation.”

Prior to European arrival more than 500 different First Nations groups inhabited the continent we now call Australia. Aboriginal Nations covered wide geographical areas and had distinct borders consisting of rivers, mountains, rocks or hills. Within these Nations were Clan groups that had more specific borders, but shared common kinship and language. And within these Clan groups, were family groups comprising a small to medium group of kinship related men, women and children who lived and hunted together.

For thousands of years, prior to the arrival of Europeans, on the lands we inhabit today, lived many of these groups. They fished and hunted in the waters and hinterlands of this area and harvested food sustainably from the surrounding bush.

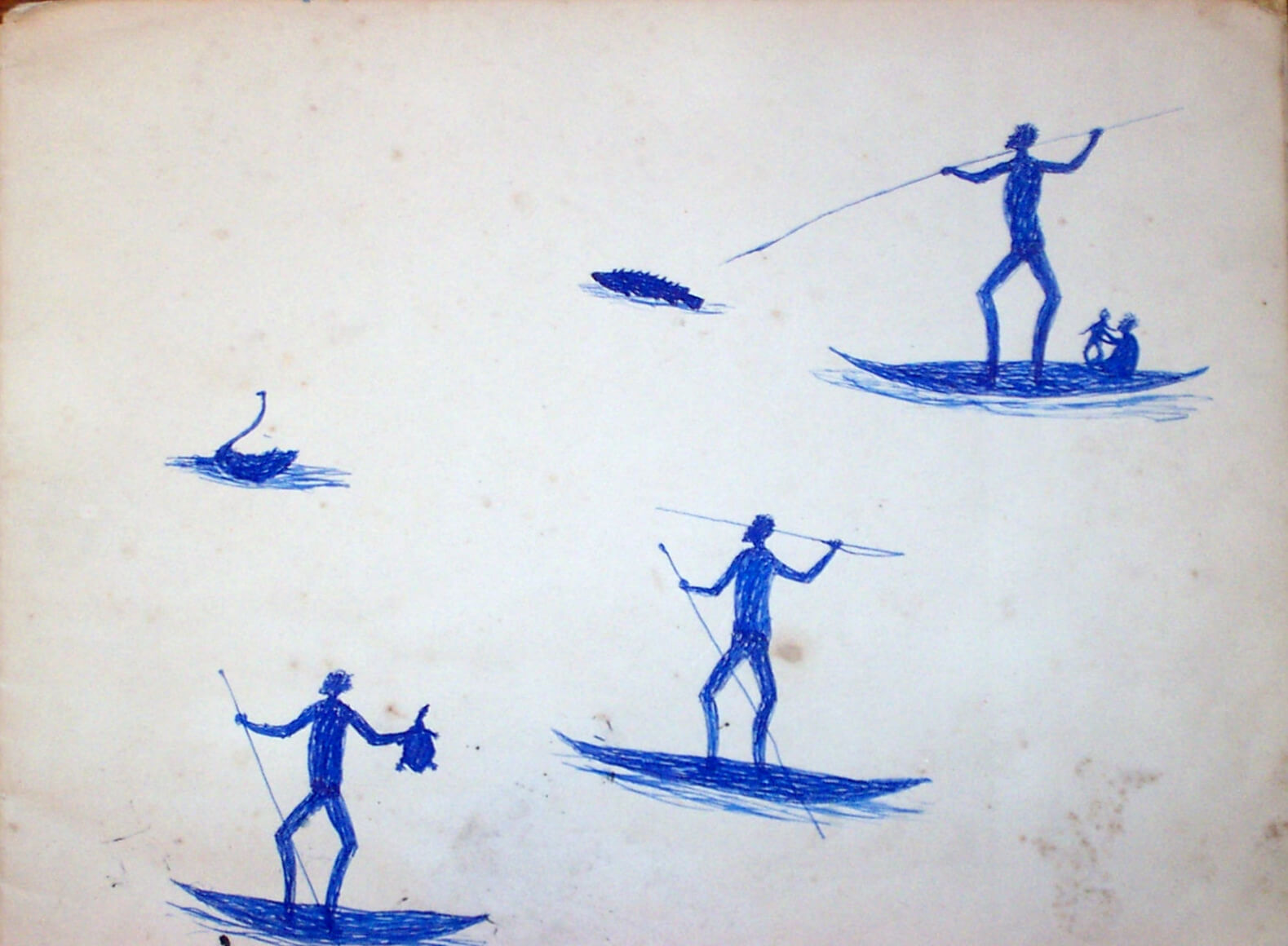

The men carried spears and spear throwers and, in some instances, boomerangs. They used canoes made from the bark of ancient trees and rafts made from local wood, bark and reeds, to be used on the waters of the Murray River and Lake Moodemere. Women’s digging sticks could double as fighting weapons and their large, deep wooden dishes held seeds, vegetables, water—or even babies.

Largely self-sufficient and harmonious, they had no need to travel far, moving across defined areas following seasonal changes that included the flowering, fruiting and seeding cycles of local plants; changes in weather, temperature and wind direction; the presence of insects; different breeding cycles; certain constellations in the night sky and even the fatness and skinniness of certain species.

Social activity involving neighbouring groups was usually in warmer periods and held at the intersection of group boundaries. Lake Moodemere; a natural billabong rich in waterfowl and surrounded by ancient red gum trees was one meeting place. Upwards of 500 men, women and children would gather for trade, ceremony, marriages, social events and to settle differences.

These groups had complex kinship systems and rules for social interaction determined by birthright, shared language, cultural obligations and responsibilities. Kinship determined how people related to one another and their surroundings, but more than a social hierarchy, a person’s position in the kinship established their relationship to the land, the animals, plants, songs, rituals, art, stories and the Lore as laid down in The Dreaming. It was this deep connection to country that defined identity and bought groups together.

First Nations history was handed down through stories, dances, myths and legends. The Dreaming was history. A history of how the world, which once featureless, was transformed into mountains, hills, valleys and waterways. How the stars were formed and how the sun came to be. The Dreaming was the basis for all the beliefs and Lore that all First Nations people chose to live their lives by.

It is estimated that there was between 300,000 and 950,000 First Nations people living in Australia at the time the British arrived in 1788. More than 250 languages and 600 dialects were spoken in over 500 different Nations.

Once European settlement began to expand inland, it had a severe and devastating effect on all First Nations groups. They were dispossessed by pastoralists and large herds of introduced animals and systematically lost access to their lands and their traditional hunting and fishing areas. Lagoons and creeks, which for centuries had only ever been fished sustainably and in season, were being fished in and out of season and breeding stocks fell. European settlers blasted the rivers to get the wool barges down, and this too drove the fish out. They died of introduced diseases to which they had no resistance, they died in random killings and organised massacres and there were rumours that the settlers were using poisons, possibly laced in flour to reduce their numbers. Cultural practices were denied, and subsequently many languages, ceremonies and songs were lost. For our First Nations people, colonisation meant massacre, violence, disease and loss.

In an attempt to protect all First Nations people from further frontier violence, colonial state governments began enacting “protectionist policies”. Initially this was by the way of establishing reserves for First Nations people to reside on and in 1859, when just 87 survivors in the North East remained, an Aboriginal Reserve at Lake Moodemere was established.

Lake Moodemere, which for millennia had been used as an important meeting place, for hunting and food gathering and ceremonial meetings, was now also the location for the distribution of unofficial rations and supplies by the colonies. Not only had First Nations peoples been subjected to a range of injustices, they were now being displaced from their traditional lands and relocated on missions and reserves in the name of protection.

Over time the Protection Board sought more power and by the end of the 19th century further laws had been passed in Parliament allowing the government to regulate who was married, where First Nations people worked, and where they could travel and eventually the removal of First Nations children from their families.

It was during this period of profound disruption, which saw the destruction and decimation of his people; that noted local First Nations artist, Tommy McRae, believed to be around 29 years of age at the time, was gifted several drawing books, along with pens and ink from Wahgunyah resident Roderick Kilborn; a Canadian Vigneron and Telegraph-master who would later become a patron of Tommy McCrae.

Tommy began sketching the landscape and images of Indigenous customs such as hunting, fighting and corroborees that were disappearing as a result of European settlement. He also sketched full of life and action images of the interactions of his people with European settlers, squatters, miners and Chinese immigrants.

Eventually his artwork made its way to Great Britain. His drawings were used to illustrate the book, Australian Legendary Tales and even today Tommy McRaes’ works are exhibited in National Galleries and Libraries around Australia.

It is believed Tommy McRae was born around 1836. As a young man he worked as a drover and stockman on Andrew Hume’s Brocklesby station (near Corowa) and travelled to Melbourne with cattle for market. But from the mid 1860s until his death on October 15th 1901, he lived at Lake Moodemere, where he earned a living through his entrepreneurial activities, selling fish, Indigenous weapons and his drawings, to the local European community.

Though no children are recorded from Tommy McCrae’s marriage with Tilly (Matilda) he and his 2nd wife Lily had four children, Sarah (named after the wife of Roderick Kilborn), who died at a young age) and then Alexander (after Kilborn’s eldest son Alec), Henry and George (also named after another of Kilborn’s sons).

During his time in Wahgunyah, Tommy became a leader of the First Nations peoples that remained. He appears in the records of the Board as a campaigner for rights, appealing for travel passes and materials for buildings, utilising the assistance of sympathetic European neighbours and local members of Parliament.

But despite being a man of integrity, who was respected by all who knew him, First Nations and Europeans alike, a non-drinker, a hard worker, an expert fisherman and man who had saved enough money to purchase a horse and vehicle for his family, the Board still issued instructions to have his children removed.

Alec was sent to Lake Tyers Aboriginal Mission and in one attempt to try and prevent the remaining children from being taken, Tommy and his wife Lily fled to Corowa, in NSW, to escape the jurisdiction of the Victorian Board. When they returned later that same year, because they were not eligible for the rations issued by the Victorian Board in NSW, one of his children was removed by police. They went back to Corowa and when they again tried to return to Lake Moodemere, their remaining child was seized. Both were sent to Koondrook, across the Murray River from Barham. Tommy McRae turned to Roderick Kilborn to prevent these seizures but nothing could be done and Tommy McRae never saw his children again.

The forced removal of First Nations children from families like Tommy and Lily McRae, between the 1890’s and the 1970’s was one of the darkest chapters of Australian history. Language, traditions, knowledge, dances and spirituality can only live on, if it can be passed to the children. By removing First Nations children from their families, these Acts essentially stole our First Nations people’s futures.

For 60,000 years, one of the oldest living cultures in the world developed a rich and complex ritual life; language, customs and Lore – the heart of which was the intimate spiritual connection to land. The land was the giver of life that provided everything that was needed. Yet it took less than 200 years to dispossess and displace our First Nations peoples, to deny them of their cultural practices and to separate them from their families and homelands.

We must gain a deeper understanding of this truly rich culture and remember and teach the history that has gone before us. History is not there for us to like or dislike. It is there for us to learn from. Only then will we build stronger connections between our First Nations peoples and the broader community and only then can we shift perceptions and develop a national narrative of unity and respect.

Artist Tommy McRae. Picture provided by the Wahgunyah Historical Society – Kilborn Album 12

Artist Tommy McRae. Picture provided by the Wahgunyah Historical Society – Kilborn Album 09

Artist Tommy McRae. Picture provided by the Wahgunyah Historical Society – Kilborn Album A566

Artist Tommy McRae. Picture provided by the Wahgunyah Historical Society – Kilborn Album 1

Tommy McRae Portrait